To understand the process of a hypothesis tests, you need to first have an understanding of what a hypothesis is, which is an educated guess about a parameter. Once you have the hypothesis, you collect data and use the data to make a determination to see if there is enough evidence to show that the hypothesis is true. However, in hypothesis testing you actually assume something else is true, and then you look at your data to see how likely it is to get an event that your data demonstrates with that assumption. If the event is very unusual, then you might think that your assumption is actually false. If you are able to say this assumption is false, then your hypothesis must be true. This is known as a proof by contradiction. You assume the opposite of your hypothesis is true and show that it can’t be true. If this happens, then your hypothesis must be true. All hypothesis tests go through the same process. Once you have the process down, then the concept is much easier. It is easier to see the process by looking at an example. Concepts that are needed will be detailed in this example.

Example \(\PageIndex<1>\) basics of hypothesis testing Suppose a manufacturer of the XJ35 battery claims the mean life of the battery is 500 days with a standard deviation of 25 days. You are the buyer of this battery and you think this claim is inflated. You would like to test your belief because without a good reason you can’t get out of your contract. What do you do? Solution Well first, you should know what you are trying to measure. Define the random variable. Let x = life of a XJ35 battery Now you are not just trying to find different x values. You are trying to find what the true mean is. Since you are trying to find it, it must be unknown. You don’t think it is 500 days. If you did, you wouldn’t be doing any testing. The true mean, \(\mu\), is unknown. That means you should define that too. Let \(\mu\)= mean life of a XJ35 battery Now what? You may want to collect a sample. What kind of sample? You could ask the manufacturers to give you batteries, but there is a chance that there could be some bias in the batteries they pick. To reduce the chance of bias, it is best to take a random sample. How big should the sample be? A sample of size 30 or more means that you can use the central limit theorem. Pick a sample of size 30. Example \(\PageIndex<1>\) contains the data for the sample you collected:

| 491 | 485 | 503 | 492 | 282 | 490 |

| 489 | 495 | 497 | 487 | 493 | 480 |

| 483 | 504 | 501 | 486 | 478 | 492 |

| 482 | 502 | 485 | 503 | 497 | 500 |

| 488 | 475 | 478 | 490 | 487 | 486 |

Now what should you do? Looking at the data set, you see some of the times are above 500 and some are below. But looking at all of the numbers is too difficult. It might be helpful to calculate the mean for this sample. The sample mean is \(\overline

Definition \(\PageIndex<1>\) Null Hypothesis: historical value, claim, or product specification. The symbol used is \(H_\).

For this problem: \(H_

.png?revision=1)

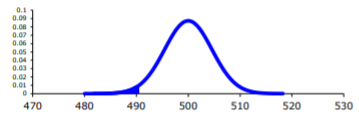

Now back to the mean. You have a sample mean of 490 days. Is this small enough to believe that you are right and the manufacturer is wrong? How small does it have to be? If you calculated a sample mean of 235, you would definitely believe the population mean is less than 500. But even if you had a sample mean of 435 you would probably believe that the true mean was less than 500. What about 475? Or 483? There is some point where you would stop being so sure that the population mean is less than 500. That point separates the values of where you are sure or pretty sure that the mean is less than 500 from the area where you are not so sure. How do you find that point? Well it depends on how much error you want to make. Of course you don’t want to make any errors, but unfortunately that is unavoidable in statistics. You need to figure out how much error you made with your sample. Take the sample mean, and find the probability of getting another sample mean less than it, assuming for the moment that the manufacturer is right. The idea behind this is that you want to know what is the chance that you could have come up with your sample mean even if the population mean really is 500 days. You want to find \(P\left(\overline

Definition \(\PageIndex<3>\) Test Statistic: \(z=\dfrac<\overline

Definition \(\PageIndex<4>\) p – value: probability that the test statistic will take on more extreme values than the observed test statistic, given that the null hypothesis is true. It is the probability that was calculated above.

Now, how small is small enough? To answer that, you really want to know the types of errors you can make. There are actually only two errors that can be made. The first error is if you say that \(H_

| \(H_\) true | \(H_\) false | |

| Reject \(H_\) | Type 1 error | No error |

| Fail to reject \(H_\) | No error | Type II error |

Now how do you find \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\)? Well \(\alpha\) is actually chosen. There are only three values that are usually picked for \(\alpha\): 0.01, 0.05, and 0.10. \(\beta\) is very difficult to find, so usually it isn’t found. If you want to make sure it is small you take as large of a sample as you can afford provided it is a representative sample. This is one use of the Power. You want \(\beta\) to be small and the Power of the test is large. The Power word sounds good.

Which pick of \(\alpha\) do you pick? Well that depends on what you are working on. Remember in this example you are the buyer who is trying to get out of a contract to buy these batteries. If you create a type I error, you said that the batteries are bad when they aren’t, most likely the manufacturer will sue you. You want to avoid this. You might pick \(\alpha\) to be 0.01. This way you have a small chance of making a type I error. Of course this means you have more of a chance of making a type II error. No big deal right? What if the batteries are used in pacemakers and you tell the person that their pacemaker’s batteries are good for 500 days when they actually last less, that might be bad. If you make a type II error, you say that the batteries do last 500 days when they last less, then you have the possibility of killing someone. You certainly do not want to do this. In this case you might want to pick \(\alpha\) as 0.10. If both errors are equally bad, then pick \(\alpha\) as 0.05.

The above discussion is why the choice of \(\alpha\) depends on what you are researching. As the researcher, you are the one that needs to decide what \(\alpha\) level to use based on your analysis of the consequences of making each error is.

If a type I error is really bad, then pick \(\alpha\) = 0.01.

If a type II error is really bad, then pick \(\alpha\) = 0.10

If neither error is bad, or both are equally bad, then pick \(\alpha\) = 0.05

The main thing is to always pick the \(\alpha\) before you collect the data and start the test.

The above discussion was long, but it is really important information. If you don’t know what the errors of the test are about, then there really is no point in making conclusions with the tests. Make sure you understand what the two errors are and what the probabilities are for them.

Now it is time to go back to the example and put this all together. This is the basic structure of testing a hypothesis, usually called a hypothesis test. Since this one has a test statistic involving z, it is also called a z-test. And since there is only one sample, it is usually called a one-sample z-test.

Example \(\PageIndex\) battery example revisited

Solution

1. x = life of battery

\(\mu\) = mean life of a XJ35 battery

2. \(H_ : \mu=500\) days

\(\alpha = 0.10\) (from above discussion about consequences)

3. Every hypothesis has some assumptions that be met to make sure that the results of the hypothesis are valid. The assumptions are different for each test. This test has the following assumptions.

4. The test statistic depends on how many samples there are, what parameter you are testing, and assumptions that need to be checked. In this case, there is one sample and you are testing the mean. The assumptions were checked above.

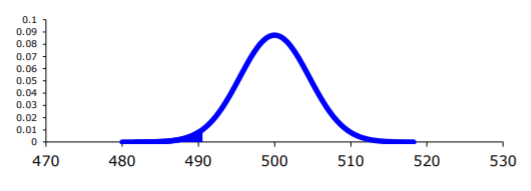

.png?revision=1)

5. Now what? Well, this p-value is 0.0142. This is a lot smaller than the amount of error you would accept in the problem -\(\alpha\) = 0.10. That means that finding a sample mean less than 490 days is unusual to happen if \(H_\) is true. This should make you think that \(H_\) is not true. You should reject \(H_\).

In fact, in general:

Fail to reject \(H_\) if the p-value \(\geq \alpha\).

6. Since you rejected \(H_\), what does this mean in the real world? That is what goes in the interpretation. Since you rejected the claim by the manufacturer that the mean life of the batteries is 500 days, then you now can believe that your hypothesis was correct. In other words, there is enough evidence to show that the mean life of the battery is less than 500 days.

Now that you know that the batteries last less than 500 days, should you cancel the contract? Statistically, there is evidence that the batteries do not last as long as the manufacturer says they should. However, based on this sample there are only ten days less on average that the batteries last. There may not be practical significance in this case. Ten days do not seem like a large difference. In reality, if the batteries are used in pacemakers, then you would probably tell the patient to have the batteries replaced every year. You have a large buffer whether the batteries last 490 days or 500 days. It seems that it might not be worth it to break the contract over ten days. What if the 10 days was practically significant? Are there any other things you should consider? You might look at the business relationship with the manufacturer. You might also look at how much it would cost to find a new manufacturer. These are also questions to consider before making any changes. What this discussion should show you is that just because a hypothesis has statistical significance does not mean it has practical significance. The hypothesis test is just one part of a research process. There are other pieces that you need to consider.

That’s it. That is what a hypothesis test looks like. All hypothesis tests are done with the same six steps. Those general six steps are outlined below.

Sorry, one more concept about the conclusion and interpretation. First, the conclusion is that you reject \(H_\) or you fail to reject \(H_\). Why was it said like this? It is because you never accept the null hypothesis. If you wanted to accept the null hypothesis, then why do the test in the first place? In the interpretation, you either have enough evidence to show \(H_\) is true, or you do not have enough evidence to show \(H_\) is true. You wouldn’t want to go to all this work and then find out you wanted to accept the claim. Why go through the trouble? You always want to show that the alternative hypothesis is true. Sometimes you can do that and sometimes you can’t. It doesn’t mean you proved the null hypothesis; it just means you can’t prove the alternative hypothesis. Here is an example to demonstrate this.

Example \(\PageIndex\) conclusion in hypothesis tests

In the U.S. court system a jury trial could be set up as a hypothesis test. To really help you see how this works, let’s use OJ Simpson as an example. In the court system, a person is presumed innocent until he/she is proven guilty, and this is your null hypothesis. OJ Simpson was a football player in the 1970s. In 1994 his ex-wife and her friend were killed. OJ Simpson was accused of the crime, and in 1995 the case was tried. The prosecutors wanted to prove OJ was guilty of killing his wife and her friend, and that is the alternative hypothesis

Solution

\(H_\): OJ is innocent of killing his wife and her friend

In this case, a verdict of not guilty was given. That does not mean that he is innocent of this crime. It means there was not enough evidence to prove he was guilty. Many people believe that OJ was guilty of this crime, but the jury did not feel that the evidence presented was enough to show there was guilt. The verdict in a jury trial is always guilty or not guilty!

The same is true in a hypothesis test. There is either enough or not enough evidence to show that alternative hypothesis. It is not that you proved the null hypothesis true.

When identifying hypothesis, it is important to state your random variable and the appropriate parameter you want to make a decision about. If count something, then the random variable is the number of whatever you counted. The parameter is the proportion of what you counted. If the random variable is something you measured, then the parameter is the mean of what you measured. (Note: there are other parameters you can calculate, and some analysis of those will be presented in later chapters.)

Example \(\PageIndex\) stating hypotheses

Identify the hypotheses necessary to test the following statements:

Solution

a. x = salary of teacher

\(\mu\) = mean salary of teacher

The guess is that \(\mu>\$ 30,000\) and that is the alternative hypothesis.

The null hypothesis has the same parameter and number with an equal sign.

b. x = number od students who like math

p = proportion of students who like math

c. x = age of students in this class

\(\mu\) = mean age of students in this class

The guess is that \(\mu \neq 21\) and that is the alternative hypothesis.

Example \(\PageIndex\) Stating Type I and II Errors and Picking Level of Significance

Solution

a. x = time to first berry for YumYum Berry plant

\(\mu\) = mean time to first berry for YumYum Berry plant

Type I Error: If the corporation does a type I error, then they will say that the plants take longer to produce than 90 days when they don’t. They probably will not want to market the plants if they think they will take longer. They will not market them even though in reality the plants do produce in 90 days. They may have loss of future earnings, but that is all.

Type II error: The corporation do not say that the plants take longer then 90 days to produce when they do take longer. Most likely they will market the plants. The plants will take longer, and so customers might get upset and then the company would get a bad reputation. This would be really bad for the company.

Level of significance: It appears that the corporation would not want to make a type II error. Pick a 10% level of significance, \(\alpha = 0.10\).

b. x = number of Aboriginal prisoners who have died

p = proportion of Aboriginal prisoners who have died

Type I error: Rejecting that the proportion of Aboriginal prisoners who died was 0.27%, when in fact it was 0.27%. This would mean you would say there is a problem when there isn’t one. You could anger the Aboriginal community, and spend time and energy researching something that isn’t a problem.

Type II error: Failing to reject that the proportion of Aboriginal prisoners who died was 0.27%, when in fact it is higher than 0.27%. This would mean that you wouldn’t think there was a problem with Aboriginal prisoners dying when there really is a problem. You risk causing deaths when there could be a way to avoid them.

Level of significance: It appears that both errors may be issues in this case. You wouldn’t want to anger the Aboriginal community when there isn’t an issue, and you wouldn’t want people to die when there may be a way to stop it. It may be best to pick a 5% level of significance, \(\alpha = 0.05\).

Hypothesis testing is really easy if you follow the same recipe every time. The only differences in the various problems are the assumptions of the test and the test statistic you calculate so you can find the p-value. Do the same steps, in the same order, with the same words, every time and these problems become very easy.

For the problems in this section, a question is being asked. This is to help you understand what the hypotheses are. You are not to run any hypothesis tests and come up with any conclusions in this section.

5. See solutions

7. See solutions

This page titled 7.1: Basics of Hypothesis Testing is shared under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by Kathryn Kozak via source content that was edited to the style and standards of the LibreTexts platform.